And here I am again, once again, yes again, left empty-handed. I walked all the way out to Yuri's house and I was so exhausted when I got there that he rushed out to greet me with a cold washcloth. Dabbing my eyes and nose, he said, "Oh, my dear old friend Pal, look at you, look at your face! You look like a merry little hiking man, your face, so healthy! But no, you are not healthy at all, you have boils and sores and they only appear as healthy, poor lovely Pal!"

We ran inside quickly and I sat on a stool in his kitchen while he looked through his soda cabinet for a cool and refreshing bottle of Mint Z, which he served to me in a short glass on a hot towel. "Okay, here you go, poor Pal," he said.

A moment later, he was deep inside his biscuit drawer, rummaging around for me, insistent that we share a garlic roll. All the biscuits were nicely lined-up in there, labelled, in order of practicality, and he tapped along the little rows of bread tops, wielding a smart pair of tongs with a tartan handle.

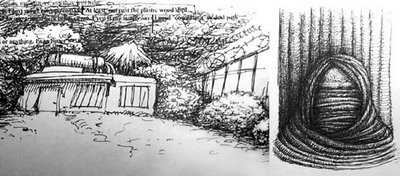

"Oh, Yuri, it's good to see you," I yelled, with loft, carrying my voice high, along the ceiling, so he could hear me there as he leaned so deep inside the drawer. "I must remember to see your magnificent animated deer. I've really found myself in a excited stare lately whenever I think about it. And at length I am! Is the deer here somewhere? Don't you remember your little deer puppet? It was about five inches tall or so. You had it in a pair of little tree trunk pants. Have you already forgotten? Please tell me you're still working on the film. I must know. Will there be a sequel I wonder? You might at least allude to a sequel. The Second Deer and The Corollary Second Potion. Oh, the happy pitter-patter of children's feet racing to get in line! I wouldn't actually produce it were I you, though. You should be done with it and retreat into the woods."

The coolness of the washcloth was terrifically invigorating and I found myself at full energy once again, wearing a most patent grin and, after wringing it out sufficiently, I draped the little cloth over my hand to let it dry in the nice kitchen breeze of the afternoon.

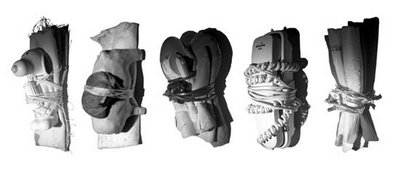

"If you want to see the deer," came out Yuri's voice from the drawer, "well, he has grown quite fat." His English is not so well as mine and, given all things, I think he meant that the corporeal character he fashioned for the claymation had fallen apart and slumped and now looked nearly burst from his vast swallowings of entropy. Yuri emerged with a cinnamon bear claw for me, served on a deli-thin slice of cork board. "What are deer? They run past us, that's all. But it is humans, which also run past us. But which are us!"

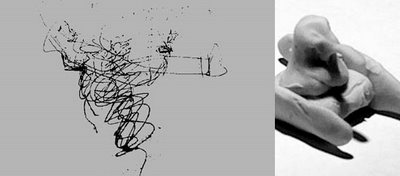

He waved me on and wandered into his editing room. I moved the washcloth to my shoulder, held out the biscuit, the soda, the towel and the cork board, and followed close behind. He reached down to his desk (his editing desk, I concluded) and snapped on a small monitor, a little blue screen which popped out from a boxy black shell. A razor sat on the desk as well. Also, next to the razor, so many remote controls banded together into a single, impenetrable family unit.

"Here is what I mean, and what is amazing to me," he said, with cold conviction, peering at me with low eyes, upon a sinister but still pouty frown. The screen fired up with presentation of a little blue film about a woman who travelled from town-to-town, visiting banquets and free continental breakfasts. She had an Amtrak Gold card with Premier Coach endorsements. So she went all over, wherever food was. The breakfasts were fine, she ate conservatively and kept a low profile. But, later, at the banquet, she would wait until the lights were off and it was dark in the banquet hall. And the camera would show that it was dead quiet, dark, so very dark, and the food was still glistening, but everyone had gone home. Except her, who said she'd clean up. "See how real," said Yuri Hollops, not meaning that this was a true story, but informing me that the actors were actual mammalian peopleforms, not clay or melon.

I think what really intrigued Yuri about the film were the camera angles. This lady would go on her night binges, devouring everything except the darkness itself, plowing through trays, often without taking a moment to lift the lid, just deflecting it away with her snapping jaws. The cinematographer would get right in there and shoot the film right at the vantage point inside her mouth, somewhere along her top teeth. So the lens would peer out, catching an inside shot of the bottom row of teeth while great gobs of ranch dressing and subway sandwiches and pretzels would ooze across the screen, splattering the view, while you -- well, you're right there in the center of action. And then, suddenly the camera's clean and you're back in a nice, new mouth, diving off into a wall of lobster tails and creamed duck.

This gave us much to talk about when we retired to his dressing room. I sprawled comfortable across the sofa, resting my elbow upon the wonderfully dry washcloth, while he dissected pressing matters at hand, how mastery is ultimately revealed only by shooting film in the dark and the symbols at play when a whole theatric audience is cast, without argument, as the mouth. Naturally, legal implications, fair use (of the audience by the filmmaker.) I brought up the cleansing of the lenses -- good lord, what an undertaking -- and this provoked a very thoughtful discussion that lasted a solid fifteen minutes.

Soon I was ready to go and only required a bit of masking tape to hold shut the clasp for one of my shoes. I was out the door, propped forward on an eastward route, when I suddenly remembered the deer photos I had promised the young reporter, as well as some sneak footage, gah! I jostled Yuri's door with great effort, but it was locked fast.